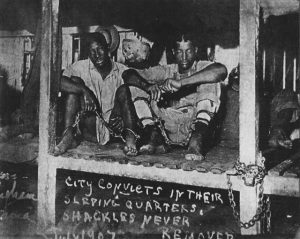

In 1865 the 13th amendment abolished slavery except as punishment for someone convicted of a crime . The crimes that people were convicted of were ridiculous (being recently “freed” from slavery, but arrested and convicted for not yet having found employment). So convict leasing as a form of slavery continued. And basically still exists. If you don’t understand this point in history, I highly recommend educating yourself. It is critical to understanding the present moment and recognizing how much of this country was literally built by enslaved Africans and African Americans. This recent finding in the article below also further illustrates the lengths those with power have gone to in order to hide and obscure the truth of this practice and the treatment of people.

In 1865 the 13th amendment abolished slavery except as punishment for someone convicted of a crime . The crimes that people were convicted of were ridiculous (being recently “freed” from slavery, but arrested and convicted for not yet having found employment). So convict leasing as a form of slavery continued. And basically still exists. If you don’t understand this point in history, I highly recommend educating yourself. It is critical to understanding the present moment and recognizing how much of this country was literally built by enslaved Africans and African Americans. This recent finding in the article below also further illustrates the lengths those with power have gone to in order to hide and obscure the truth of this practice and the treatment of people.

From the article: Bodies believed to be those of 95 black forced-labor prisoners from Jim Crow era unearthed in Sugar Land

” The convict-leasing system proliferated across the south in the late 19th century and into the 20th, overwhelmingly targeting black Americans picked up for offenses such as vagrancy, flirting with white women or petty theft, as historian Douglas A. Blackmon reported in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “Slavery by Another Name.” The prisoners were then leased by the state to private businessmen and forced to work on plantations, in coal mines and railroads, or on other state projects — such as building the entire Texas Capitol building from scratch.

When the state leased convicts out to private contractors, they had no financial interest in the health or welfare of the people working for them,” said W. Caleb McDaniel, a history professor at Rice University in Houston. “And so the convict-leasing system saw extremely high levels of mortality and sickness under convict lessees. If the prisoner died, they would simply go back to the state and say, ‘You owe us another prisoner.’ ”

From sunup to sundown, convicts who were leased by the state to plantation owners toiled in the fields chopping sugar cane sometimes until they “dropped dead in their tracks,” as the State Convention of Colored Men of Texas complained in 1883.

Reginald Moore, started researching Sugar Land’s slavery and convict-leasing history after spending time working as a prison guard at one of Texas’s oldest prisons, and his curiosity intensified. He had a hunch. Based on what he learned, he believed that the bodies of former slaves and black prisoners were still buried in Sugar Land’s backyard.

For 19 years, he searched for their bodies, stopping just short of sticking a shovel in the dirt himself.

At the former Imperial State Prison Farm site, archaeologists have unearthed an entire plot of precise rectangular graves for 95 souls, each buried two to five feet beneath the soil in nearly disintegrated pinewood caskets. The 19th-century cemetery was unmarked, with no vestige of its existence visible from the surface.

But more crucially, he said, it vindicates the prisoners whose backbreaking work helped rebuild the state of Texas in the ruins of the post-Civil War era without so much as a proper burial to acknowledge their contributions.

“This is a completely rare site. It’s going to change how we think about Texas history and how we think about ourselves and how we built this state, how all of us built this state.”